A Sovereign Aspiration: Deconstructing the Somaliland-Somalia Impasse and the Shifting Geopolitics of the Horn of Africa

Summary

Table of Contents

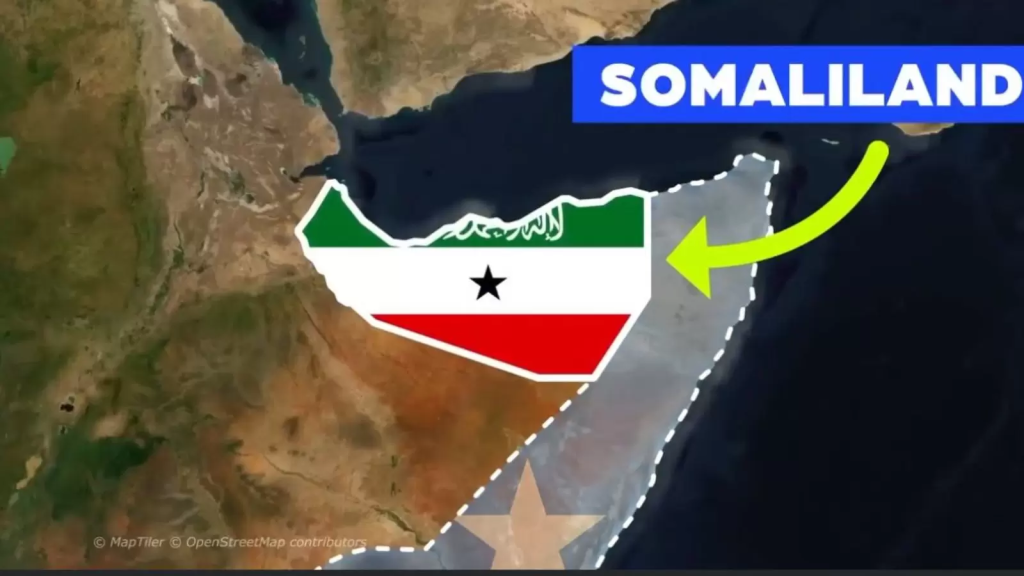

The relationship between the self-declared Republic of Somaliland and the Federal Republic of Somalia represents one of Africa’s most enduring and complex sovereignty disputes. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the historical, legal, political, and geopolitical dimensions of this impasse. It argues that the issue has evolved from a dormant post-colonial dispute into an active geopolitical flashpoint, driven by the strategic imperatives of regional and global powers.

The origins of the conflict are rooted in the divergent colonial legacies of British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland, which culminated in a legally and politically flawed union in 1960. Decades of political marginalization and the genocidal campaign waged by the Siad Barre regime against the Isaaq clan of the north irrevocably severed the social contract, leading to Somaliland’s 1991 declaration to restore its sovereignty. Since then, Somaliland has built a remarkably stable, democratic de facto state, standing in stark contrast to the chronic instability and conflict that has plagued southern Somalia.

Somaliland’s case for statehood is legally robust, meeting the criteria of the Montevideo Convention and uniquely framed as the dissolution of a voluntary union, not a secession. This distinction allows it to align with the African Union’s principle of upholding colonial-era borders. However, the international community, led by the African Union (AU) and the United States, has withheld recognition, primarily due to the political fear of setting a precedent for other secessionist movements on the continent—a “Pandora’s Box” scenario. This policy of non-recognition has created a diplomatic stalemate, perpetuating a legal fiction that hinders Somaliland’s development and regional stability.

This long-standing status quo has been shattered by the January 2024 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Somaliland and Ethiopia. Driven by Ethiopia’s existential need for sea access, the agreement trades a potential grant of recognition for a naval base on Somaliland’s coast. This transactional approach to sovereignty has fundamentally altered the regional calculus, forcing a re-evaluation of the “One Somalia” policy. It has triggered a fierce diplomatic backlash from Mogadishu and catalyzed a regional realignment, with Somalia bolstering alliances with Egypt and Turkey to counter the emerging Ethiopia-Somaliland-UAE axis

.

The Horn of Africa has thus become a theater for the geopolitical rivalries of Middle Eastern powers and the strategic competition between the United States and China. For the U.S., Somaliland’s stability, democratic credentials, and strategic location offer a compelling alternative to its strained position in Djibouti and a counterweight to Chinese influence. For actors like the UAE and Israel, Somaliland is a key node in a network designed to secure maritime trade routes and project power in the Red Sea corridor.

This report concludes that the protracted status quo is no longer tenable. The Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU has introduced an era of high-stakes diplomacy and heightened risk of conflict. A resolution will require a paradigm shift away from the rigidities of the past. The international community, particularly the AU and the U.S., must move beyond a policy of containment and actively mediate a final status agreement that acknowledges the de facto reality of Somaliland’s existence while addressing the legitimate concerns of Somalia regarding regional stability. Failure to do so risks allowing the dispute to be fully consumed by proxy rivalries, with devastating consequences for the entire Horn of Africa.

I. The Fault Line of History: From Colonial Division to a Flawed Union (1884-1969)

The contemporary schism between Somaliland and Somalia is not a recent phenomenon but the culmination of distinct historical trajectories forged during the colonial era and cemented by the failures of a post-colonial union. The fundamental impasse in their relationship stems from two irreconcilable conceptions of statehood, each rooted in a different historical origin story. For Somaliland, its identity is anchored in a brief, internationally recognized period of sovereignty in 1960, preceding a voluntary union. For Somalia, its national identity was born from the very act of that union, the first step in a grander pan-Somali nationalist project. Understanding this foundational divergence is critical to deconstructing the current conflict.

A Tale of Two Protectorates: British Indirect Rule vs. Italian Colonialism

The “Scramble for Africa” in the late 19th century partitioned the ethnically homogenous Somali-inhabited territories among Britain, Italy, France, and Ethiopia. The two largest entities, British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland, developed under starkly different colonial philosophies, creating divergent political, administrative, and economic cultures.

The British Somaliland Protectorate, established in 1884, was governed primarily for strategic purposes: to secure a supply of livestock for its garrison in Aden and to deny control of the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden to other European powers. London employed a system of indirect rule, administering the territory with a light footprint, preserving traditional clan structures, and investing minimally in infrastructure or economic development. The result was a society where indigenous governance systems remained robust, and the experience of colonial statehood was limited and largely non-intrusive.

In contrast, Italian Somaliland was administered as a formal colony with ambitions of settlement and economic exploitation. Italian rule was more direct, interventionist, and often violent, seeking to establish a plantation economy and fundamentally restructure local society. Rome invested more heavily in infrastructure and a centralized bureaucracy, but this came at the cost of suppressing local autonomy and imposing a foreign legal and administrative system. These differing experiences meant that by 1960, the two territories were distinct polities with separate languages of administration (English and Italian), different legal codes, and dissimilar political expectations.

The Pan-Somali Dream and the Hasty Union of 1960

In the mid-20th century, a powerful wave of pan-Somali nationalism swept the region. The vision was the creation of a “Greater Somalia” that would unite all five Somali-inhabited territories into a single nation-state. This potent ideal fueled the drive for independence and unification.

On June 26, 1960, the British Somaliland Protectorate became the independent State of Somaliland. It immediately received international recognition from 35 countries, including all five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. The United States, while not extending formal recognition due to the expected short duration of its independence, sent a congratulatory message from Secretary of State Herter. Five days later, on July 1, 1960, the former Italian trust territory gained its independence. On that same day, driven by the pan-Somali dream, the State of Somaliland voluntarily merged with its southern counterpart to form the Somali Republic.

The Unratified “Act of Union”: A Contested Legal Foundation

The legal basis of this new republic was precarious from its inception. The union was not the product of careful negotiation but of a rushed, emotion-driven process where nationalist fervor overshadowed the necessary legal and administrative groundwork. This haste created a foundational weakness that was immediately exploited by the more powerful southern political elite, making future conflict almost inevitable.

Delegates from the north and south signed different versions of the Act of Union, agreeing to different terms. The legislature of the newly independent State of Somaliland passed a “Union of Somaliland and Somalia Law,” but the authorized representative from the south never signed this treaty. A new, unified Act of Union was only passed retrospectively by the combined National Assembly in January 1961, six months after the fact.

Crucially, Somaliland maintains that this union was never legally ratified by both parties as an international treaty between two sovereign states. This position was later supported by a 2005 African Union fact-finding mission, which concluded that “the fact that the ‘union between Somaliland and Somalia was never ratified’…makes Somaliland’s search for recognition historically unique”. This legal lacuna is a cornerstone of Somaliland’s contemporary argument that its 1991 declaration was not an act of secession but a legal dissolution of a flawed and unratified union.

Early Discontent and Political Marginalization of the North

The imbalances in the union became apparent almost immediately. The more populous south dominated the new state’s political and economic life. Mogadishu, nearly 2,000 miles from Hargeisa, was chosen as the national capital, centralizing government services and relegating the north to a peripheral status. Key political and military positions were awarded disproportionately to southerners. The first president and prime minister were both from the south.

This southern dominance was codified in the new constitution, which was drafted primarily in the south with only marginal input from northern politicians. The deep northern resentment was starkly revealed in the June 1961 constitutional referendum. In Somaliland, turnout was extremely low, with only about 100,000 people voting, and the overwhelming majority of those who did cast their ballots rejected the constitution. In contrast, the south returned a massive vote in favor, with numbers so high as to suggest electoral fraud. This clear rejection of the new state’s foundational document, just one year into the union, was a powerful signal of the north’s profound disenchantment. The simmering discontent erupted into violence later that year when a group of highly qualified Somaliland military officers attempted a coup, which was ultimately suppressed. This event marked the first violent expression of the north’s grievance and foreshadowed the decades of conflict to come.

Table 1: Timeline of Key Events in Somaliland-Somalia Relations (1884-Present)

| Date/Period | Event | Significance |

| 1884 | Establishment of British Somaliland Protectorate. | Creates a distinct colonial entity with defined borders, separate from Italian-controlled areas. This forms the basis of Somaliland’s modern territorial claim. |

| June 26, 1960 | State of Somaliland gains independence from Britain. | Achieves brief but widespread international recognition as a sovereign state, a key pillar of its legal argument for renewed statehood. |

| July 1, 1960 | Voluntary union with former Italian Somaliland to form the Somali Republic. | The union, driven by pan-Somali nationalism, is legally flawed and unratified, creating the basis for future disputes over its legitimacy. |

| 1961 | Constitutional referendum is rejected in the north; northern officers attempt a coup. | Early, clear signs of northern discontent with southern political dominance and the terms of the union. |

| October 21, 1969 | Major General Siad Barre leads a military coup. | Ends the democratic era and ushers in a military dictatorship that becomes increasingly repressive and clan-based, centralizing power in Mogadishu. |

| 1981 | Somali National Movement (SNM) is founded. | An Isaaq-led armed resistance group is formed to overthrow the Barre regime, marking the beginning of the Somaliland War of Independence. |

| 1988-1989 | The Isaaq Genocide. | The Barre regime carries out a systematic and brutal campaign against the Isaaq clan, killing tens of thousands and destroying northern cities. This is the “point of no return” for Somaliland. |

| May 18, 1991 | Somaliland declares the restoration of its sovereignty. | Following the collapse of the Somali state, Somaliland withdraws from the union and re-asserts the independence it held in 1960. |

| May 31, 2001 | Constitutional Referendum held in Somaliland. | A 97% vote in favor of a new constitution reaffirms independence and establishes a multi-party democratic system, providing a popular mandate for statehood. |

| January 1, 2024 | Ethiopia-Somaliland Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) is signed. | A landmark agreement potentially trading Ethiopian recognition for a naval base. It shatters the regional status quo and triggers a major diplomatic crisis with Somalia. |

| April 2025 | Somaliland suspends all dialogue with Somalia. | Citing provocations by the Somali Prime Minister, Somaliland officially halts the long-stalled talks, signaling a definitive shift away from a negotiated settlement with Mogadishu. |

II. The Unraveling: Dictatorship, Genocide, and the Collapse of the Somali State (1969-1991)

The fragile union of the 1960s disintegrated completely under the weight of a brutal military dictatorship that systematically dismantled the country’s nascent democratic institutions and targeted its own citizens. The events between 1969 and 1991, culminating in state-sponsored genocide and the total collapse of the central government, did not merely cause a political separation; they created a moral and psychological chasm between Somaliland and Somalia that remains unbridgeable to this day.

The Siad Barre Regime and the Erosion of the Social Contract

In October 1969, the commander of the Somali army, Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, overthrew the civilian government in a bloodless coup. The military junta suspended the constitution, arrested government officials, and established a Supreme Revolutionary Council. Initially, the regime was met with some popular support for its anti-corruption campaigns and promises of modernization. Barre declared a policy of “scientific socialism” and aligned Somalia with the Soviet Union, which became the principal supplier for the Somali army.

However, the regime grew increasingly authoritarian and repressive. Barre systematically dismantled clan-based loyalties in favor of loyalty to the state, but in practice, he relied heavily on his own Marehan clan and the broader Darod clan-family, marginalizing others, particularly the Isaaq clan of the north. The disastrous Ogaden War against Ethiopia in 1977-78, which ended in a humiliating defeat for Somalia, further weakened the regime. In its aftermath, Barre’s government became more paranoid and brutal in its efforts to suppress dissent.

The Somali National Movement (SNM) and the War of Independence

The political and economic marginalization of the north, combined with the regime’s increasing brutality, fueled the rise of armed opposition. In 1981, members of the Isaaq diaspora founded the Somali National Movement (SNM) in London, with the goal of overthrowing Barre’s dictatorship. The SNM, receiving support from Ethiopia, waged a decade-long guerrilla war against the Somali National Army in the northern regions. It was one of several clan-based armed groups that emerged to challenge the central government, including the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF) in the northeast (Puntland) and the United Somali Congress (USC) in the south.

The Isaaq Genocide (1988-1989): The Point of No Return

The regime’s response to the SNM insurgency was not a conventional counter-insurgency campaign but a deliberate, state-sanctioned policy of collective punishment aimed at the entire Isaaq clan. This campaign fundamentally and irrevocably broke the social contract between the government in Mogadishu and the people of the north. When a state turns its military apparatus on a specific segment of its population with the intent to destroy it, it forfeits all legitimacy to govern that population. This transformed Somaliland’s claim from one of political grievance to one of existential necessity and self-preservation.

Between 1988 and 1989, the Somali Armed Forces unleashed what is now widely referred to as the Isaaq Genocide. Barre ordered the indiscriminate aerial bombardment and artillery shelling of Hargeisa and Burao, the north’s two largest cities, reducing them to rubble. Government forces conducted mass executions, laid landmines in civilian areas, and systematically targeted Isaaq civilians. An estimated 50,000 to 100,000 civilians were killed, and at least 500,000 people were displaced, fleeing as refugees to neighboring Ethiopia. This horrific event is the central trauma in Somaliland’s modern identity and serves as the ultimate moral justification for its separation. For the people of Somaliland, the memory of the genocide makes any discussion of reunification with a state that sought their annihilation unthinkable.

The Fall of Mogadishu and the Declaration of Renewed Sovereignty

The brutal war in the north, combined with rebellions in other parts of the country, fatally weakened the Barre regime. The end of the Cold War was a direct catalyst for its final collapse. Having been propped up by both superpowers at different times, the regime lost its external support and the resources needed to sustain its repressive state apparatus.

In January 1991, the United Somali Congress (USC) drove Barre’s forces out of Mogadishu, leading to the complete collapse of the central government. As Somalia descended into a chaotic civil war between rival clan-based warlords, the SNM succeeded in taking full control of the northwest. Rather than march on Mogadishu, the SNM leadership called a “Grand Conference of the Somaliland Clans” in the city of Burao from April 27 to May 18, 1991. After extensive consultations with elders representing all the major clans of the north (Isaaq, Dhulbahante, Issa, Gadabursi, and Warsangali), the delegates unanimously agreed to withdraw from the 1960 union and restore the sovereignty of the State of Somaliland. On May 18, 1991, the Republic of Somaliland was formally declared, re-establishing its independence within the borders of the former British protectorate.

III. The Somaliland Project: Building a De Facto State in a Collapsed Neighborhood

While southern Somalia disintegrated into one of the world’s most protracted examples of state failure, Somaliland embarked on a remarkable and largely unassisted journey of state-building. Its success, built on a foundation of indigenous reconciliation and a unique blend of traditional and modern governance, represents an implicit critique of the international community’s top-down, externally-driven state-building models. This bottom-up process has produced a de facto state that meets the established international legal criteria for statehood, forming the practical and legal core of its case for recognition.

From Chaos to Cohesion: Indigenous Peace and Reconciliation

The most critical factor in Somaliland’s success was its approach to peace-making. Instead of relying on external intervention, the various Somaliland communities utilized traditional, indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms. A series of clan-based peace conferences, culminating in the major gatherings at Burao in 1991 and Borama in 1993, brought together clan elders, political leaders, and civil society representatives. This “fascinating indigenous reconciliation process” was almost unprecedented in Africa, allowing communities to address grievances, end hostilities, and establish a framework for peaceful coexistence and power-sharing. This bottom-up approach, with minimal foreign involvement, forged a durable social contract and a sense of local ownership that was absent in the south, where international interventions often failed to take root. Somaliland’s stability was not achieved in spite of its lack of recognition, but perhaps partially because of it, as isolation forced a deep-seated self-reliance.

Forging a Hybrid Democracy: Institutions, Elections, and Stability

From this foundation of peace, Somaliland constructed a unique hybrid political system. The 1993 Borama conference established a bicameral parliament that ingeniously integrated traditional and modern governance structures. It consists of an elected House of Representatives (Golaha Wakiilada) and an unelected House of Elders (Golaha Guurtida), which is responsible for security, conflict resolution, and traditional law. This hybrid model has been credited with providing long-term political stability by balancing representative democracy with the authority of traditional clan leadership.

Somaliland has since built all the institutions of a modern state. It has a democratically approved constitution, a functioning executive, legislative, and judicial branch, its own military and police force, a central bank, and its own currency, the Somaliland shilling. It has held a series of presidential, parliamentary, and local elections since 2003, many of which were deemed free and fair by international observers and have resulted in peaceful transfers of power. The 2001 constitutional referendum was a strategic masterstroke, serving both to solidify the internal social contract around independence and to present the world with an undeniable democratic mandate, with 97% of voters supporting sovereignty. This was a carefully orchestrated political statement designed to shift the burden of proof onto those who would deny recognition.

The Legal Case for Recognition: Montevideo Criteria and the Dissolution of a Union

Somaliland’s claim to statehood rests on a strong legal foundation, primarily its fulfillment of the criteria set forth in the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States. This convention is the most widely accepted codification of the requirements for statehood in customary international law. Somaliland’s government and its supporters argue that it unequivocally meets all four conditions.

Furthermore, Somaliland’s central legal argument is that its case is not one of secession, but of the dissolution of a voluntary union between two independent states. By restoring its sovereignty within the borders of the former British Somaliland Protectorate, it argues that it is upholding, not violating, the African Union’s core principle of

uti possidetis juris—the doctrine that newly formed sovereign states should retain the borders of their colonial predecessors. This unique historical and legal claim, they contend, distinguishes Somaliland from other separatist movements in Africa and provides a legitimate basis for recognition without setting a dangerous precedent.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Statehood Criteria (Montevideo Convention)

| Criterion | Somaliland’s Case | Somalia’s Counter-Argument / International Position |

| A Permanent Population | Somaliland has a stable population of approximately 4.5 million people residing within its territory. The nomadic nature of some inhabitants does not negate the legal definition of a permanent population. | This criterion is generally not contested. The population is acknowledged, but they are considered citizens of the Federal Republic of Somalia. |

| A Defined Territory | The territory is clearly defined by the borders of the former British Somaliland Protectorate, established by treaties in the 19th century and confirmed at independence in 1960. This aligns with the AU principle of respecting colonial borders. | The Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) and the international community maintain that these borders define an administrative region within Somalia, not an independent state. The territory is considered an integral part of Somalia’s sovereign territory. |

| An Effective Government | Somaliland has a stable, democratically elected government that exercises effective control over the majority of its territory. It has a constitution, a bicameral parliament, an independent judiciary, a military, and provides services to its citizens. | The international community recognizes the FGS in Mogadishu as the sole legitimate government for all of Somalia, including the territory of Somaliland. Somaliland’s government is considered a regional administration. |

| Capacity to Enter into Relations with Other States | Somaliland engages in foreign relations, maintaining representative offices in numerous countries (e.g., USA, UK, Ethiopia, Taiwan). It has signed binding international agreements, such as the port management deal with the UAE’s DP World and the 2024 MoU with Ethiopia. | Under international law, only sovereign states can conduct foreign policy and enter into treaties. Somalia argues that agreements signed by Somaliland are illegal and void, as only the FGS has the authority to do so. This position is supported by most nations. |

IV. The Somali Federal Republic: A Quest for Unity Amidst Enduring Crisis

The position of the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) on Somaliland is unwavering and absolute: it considers Somaliland an integral, albeit autonomous, region of a single, indivisible Somali Republic. This stance is rooted in the pan-Somali nationalist project and is buttressed by the consensus of the international community. However, this de jure claim of sovereignty exists in a state of paradox, as Mogadishu has been unable to exercise any de facto authority over Somaliland for more than three decades. The FGS’s diplomatic strategy has been to isolate Somaliland, block its path to recognition, and insist on dialogue framed exclusively within the context of national unity—a framework Somaliland categorically rejects.

Somalia’s Official Position: The Inviolability of Territorial Integrity

The FGS and its predecessors have consistently maintained that Somaliland’s 1991 declaration of independence is an illegal act of secession that violates both Somali constitutional law and international principles of territorial integrity. From Mogadishu’s perspective, the 1960 union was the birth of the Somali nation, and any attempt to undo it is an attack on the state’s very existence. The official foreign policy vision is of a “stable, and sovereign federal republic” with its borders intact. This position is formally supported by the United Nations, the African Union, the Arab League, and all major world powers, who continue to recognize the FGS as the sole legitimate government of all of Somalia. Somalia’s government asserts that it alone has the legal authority to enter into international treaties and manage the country’s ports and resources, rendering any agreements made by Hargeisa null and void.

The Challenge of Governance: Federalism, Clan Politics, and Insecurity

Somalia’s staunch defense of its sovereignty is severely undermined by its chronic internal weaknesses. The country operates as a federal system, but the relationship between the central government and the Federal Member States (FMS) like Puntland and Jubaland is often fraught with tension over power-sharing, resource allocation, and constitutional authority. This political fragility is compounded by pervasive insecurity. For decades, the FGS has been locked in a devastating conflict with the al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorist group, Al-Shabaab, which controls large swathes of rural southern and central Somalia and carries out frequent attacks in Mogadishu and beyond. The government’s survival and its fight against Al-Shabaab are heavily dependent on the presence of international forces (formerly ATMIS, now AUSSOM) and foreign aid. This deep-seated instability consumes the government’s resources and attention, making the projection of authority into a stable and self-governing region like Somaliland a practical impossibility. This creates a “sovereignty paradox,” where Mogadishu defends a legal claim it cannot enforce, while the international community upholds this fiction, trapping Somaliland in a state of diplomatic limbo.

The Diplomatic Response to Somaliland’s Unilateral Actions

In response to Somaliland’s increasingly assertive foreign policy, particularly the 2024 MoU with Ethiopia, the FGS has launched an aggressive diplomatic counter-offensive. It immediately condemned the deal as a “blatant violation” of its sovereignty and an “act of aggression”. Mogadishu recalled its ambassador from Addis Ababa, successfully lobbied the Arab League and Egypt for statements of support, and passed a domestic law purporting to nullify the agreement. This reaction demonstrates Somalia’s strategy of leveraging its internationally recognized status to isolate Somaliland and penalize any state that engages with it as a sovereign entity.

The State of Dialogue: Intermittent Talks and Recent Suspension

Since 2012, there have been several rounds of internationally mediated talks between high-level delegations from Mogadishu and Hargeisa, often facilitated by Turkey, the UK, or Djibouti. However, these dialogues have been sporadic and have consistently failed to produce any meaningful progress. The fundamental obstacle has always been the irreconcilable starting positions of the two sides: Somaliland will only discuss the modalities of a “two-state solution” and the future relationship between two independent neighbors, while Somalia will only entertain discussions about enhanced autonomy within a single, unified state.

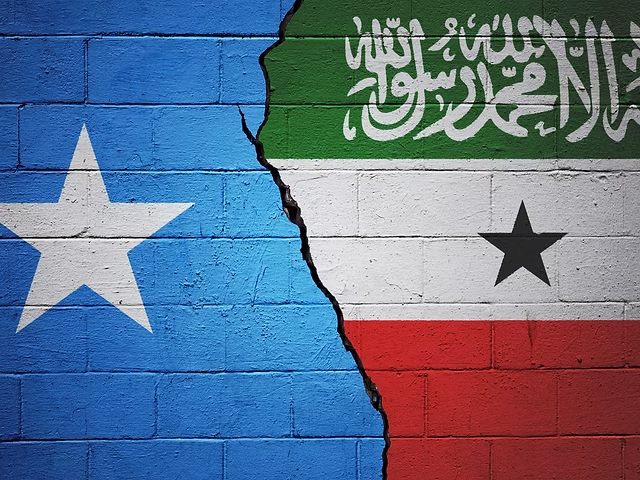

The recent Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU appears to have delivered a final blow to this moribund process. Somaliland’s decision to bypass Mogadishu and strike a strategic deal with a major regional power signals a definitive loss of faith in the dialogue framework. This was formalized in April 2025, when the Somaliland government officially suspended all future talks with Somalia. The stated trigger was a visit by Somalia’s Prime Minister Hamza Abdi Barre to Las Anod, a city in the Sool region contested between Somaliland and Puntland. Hargeisa condemned the visit as a “calculated provocation” and a “direct violation of its territorial integrity,” using it as a justification to formally withdraw from a process it already viewed as futile. This move suggests a strategic pivot by Somaliland: from seeking a negotiated settlement with Somalia to creating new geopolitical realities on the ground that force the international community to reconsider its position.

V. The International Wall of Silence: The Politics and Principles of Non-Recognition

For over three decades, Somaliland has existed as a functional and stable democracy, yet it remains unrecognized by any UN member state. This diplomatic isolation is not a result of its failure to meet the legal criteria for statehood, but rather a consequence of a powerful international consensus rooted in political caution and diplomatic inertia. The primary obstacles are the African Union’s rigid adherence to the principle of inviolable colonial borders and the long-standing “One Somalia” policy of major global powers. This has created a self-perpetuating cycle where no single actor is willing to be the first to break ranks, effectively punishing Somaliland for its success while rewarding Somalia’s legal status despite its failures.

The African Union’s Doctrine: Upholding Colonial Borders to Prevent a “Pandora’s Box”

The most significant barrier to Somaliland’s recognition is the foundational doctrine of the African Union (and its predecessor, the Organization of African Unity). The 1964 OAU resolution in Cairo established the principle of uti possidetis juris, sanctifying the colonial-era borders as permanent to prevent the continent from descending into a chaos of endless border wars and secessionist conflicts. African leaders have long feared that recognizing one breakaway state would open a “Pandora’s Box,” encouraging a cascade of secessionist movements in other multi-ethnic states, thereby threatening the fragile political fabric of the entire continent.

Somaliland has consistently argued that its case is unique and does not violate this principle. It seeks recognition based on the very same colonial borders it inherited from Britain, and it frames its action as the dissolution of a failed union, not secession. Proponents also point to the AU’s inconsistency, particularly its admission of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (Western Sahara) as a member state, a territory that never possessed prior sovereignty. Despite a 2005 AU fact-finding mission that found Somaliland’s case to be “historically unique and self-justified” , the organization has failed to act on the report, paralyzed by the fear of precedent.

The United States and the “One Somalia” Policy: A Legacy Under Review

The official policy of the United States has consistently been to support the sovereignty and territorial integrity of a single, unified Somalia. Washington has traditionally deferred to the African Union to take the lead on resolving Somaliland’s status, unwilling to unilaterally disrupt the continental consensus. The U.S. State Department has articulated the same fear of setting a dangerous precedent that could “unleash chaos” in other fragile states. This policy has been rooted in the need to maintain a partnership with the recognized government in Mogadishu for crucial counter-terrorism operations against Al-Shabaab.

However, this long-standing policy is now under serious review, creating a fundamental schism within the U.S. foreign policy establishment. While the State Department maintains its traditional, risk-averse diplomatic posture, a growing and bipartisan chorus in Congress and the national security community views the issue through the lens of great power competition. They see Somaliland’s stability, democratic governance, strategic location on the Gulf of Aden, and its burgeoning relationship with Taiwan as a significant strategic asset to counter China’s expanding influence in the region, particularly its military base in Djibouti. This has led to an increase in high-level engagement, visits by U.S. officials to Hargeisa, and the introduction of legislation aimed at strengthening U.S.-Somaliland ties and even formally recognizing its independence.

The European Union’s Pragmatic Engagement Without Recognition

The European Union’s position mirrors that of the U.S., albeit with a more pragmatic and less securitized approach. Officially, the EU and its member states support Somalia’s territorial integrity and do not recognize Somaliland. However, the EU engages directly with Hargeisa on a practical level. It has sent delegations to observe Somaliland’s elections, praising their democratic nature. Furthermore, EU missions, such as the EU Capacity Building Mission in Somalia (EUCAP Somalia), have field offices and operate in Somaliland, supporting the development of its maritime security and police sectors. EU development and cooperation funding for “Somalia” often includes programs implemented in Somaliland. This dual approach allows the EU to support Somaliland’s stability and democratic development without formally challenging the international consensus on Somali unity. The United Kingdom, as the former colonial power, maintains the closest relationship, having opened a British Office in Hargeisa and engaged in various development agreements, though it stops short of formal recognition.

VI. The New “Great Game”: Regional Powers and the Scramble for the Horn

The Horn of Africa has become a theater for a new “Great Game,” where the strategic imperatives of regional powers and the economic ambitions of Gulf states are reshaping alliances and escalating tensions. The unresolved status of Somaliland lies at the heart of this contest. Its strategic coastline, controlling access to the Bab el-Mandeb strait, has transformed it from a diplomatic curiosity into a prized geopolitical asset. The recent Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU did not create this competition, but it has dramatically accelerated it, forcing a clear alignment of regional actors into competing blocs and turning the Somaliland-Somalia dispute into a proxy battleground for broader rivalries.

Ethiopia’s Lifeline: The Strategic Imperative for Sea Access and the 2024 MoU

For Ethiopia, a nation of over 125 million people and the world’s most populous landlocked country, securing reliable and affordable access to the sea is a paramount national security interest. Since Eritrea’s independence in 1993, Ethiopia has been overwhelmingly dependent on the port of Djibouti, a situation that is both economically costly (costing an estimated $1 billion annually in fees) and strategically precarious. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has framed this issue in stark terms, calling sea access an “existential issue” for his country.

This long-standing strategic vulnerability culminated in the signing of a landmark Memorandum of Understanding with Somaliland on January 1, 2024. The agreement, though not yet a formal treaty, reportedly grants Ethiopia a 50-year lease on a 19-kilometer stretch of Somaliland’s coastline for the establishment of a naval base and commercial port access. In exchange, Ethiopia has agreed to conduct an “in-depth assessment towards taking a position” on recognizing Somaliland’s independence, a move that Somaliland’s president has publicly stated will lead to formal recognition. This agreement represents the first time a state has been willing to potentially trade formal recognition for a tangible strategic asset, fundamentally changing the dynamic of the recognition debate from a normative, legal issue to a transactional, geopolitical one. It has shattered the regional status quo and provoked a furious response from Somalia, which views it as a declaration of war on its sovereignty.

The UAE’s Commercial Empire: The Berbera Port and Geopolitical Hedging

The United Arab Emirates has become arguably the most influential external actor in Somaliland through its aggressive economic and strategic investments. This is part of a broader Emirati strategy to project power across the Red Sea and Horn of Africa, securing vital shipping lanes, countering the influence of its regional rivals Turkey and Qatar, and building a network of loyal partners.

The centerpiece of this strategy is the Port of Berbera. The UAE’s state-owned logistics giant, DP World, has invested $442 million to expand and modernize the port, transforming it into a major regional trade hub with a capacity of 500,000 containers annually. To complement this, the UAE is funding a $3 billion, 250-km railway and the Berbera Corridor highway to connect the port directly to landlocked Ethiopia, cementing its viability as a strategic alternative to Djibouti. The UAE has also established a naval base in Berbera and provides training to Somaliland’s security forces. By embedding itself so deeply into Somaliland’s economy and security architecture, the UAE is effectively treating Hargeisa as a sovereign partner, bolstering its de facto independence regardless of its de jure status.

Turkey and Egypt: Strategic Patrons of Somali Sovereignty

The Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU has catalyzed the formation of a counter-alliance aimed at defending Somali sovereignty and containing Ethiopian ambitions. Turkey, which has a deep strategic, economic, and military relationship with the FGS in Mogadishu, including its largest overseas military base, immediately reaffirmed its commitment to Somalia’s unity. While positioning itself as a mediator, Ankara’s interests are clearly aligned with Mogadishu, and it has signed a ten-year defense and economic cooperation agreement with Somalia that includes protecting its maritime waters.

Egypt, a historic rival of Ethiopia, has seized upon the crisis as an opportunity to exert pressure on Addis Ababa. The long-running and bitter dispute over Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile provides the context for Cairo’s swift and robust support for Somalia. Egypt has signed its own defense cooperation protocol with Somalia and has reportedly sent military aid, viewing the defense of Somali territorial integrity as a means to check Ethiopian regional power. This has effectively created a Somalia-Egypt-Turkey axis, backed diplomatically by the Arab League, to counter the emerging Ethiopia-Somaliland-UAE bloc.

The Puntland Dispute: A Microcosm of the Broader Conflict (Clan vs. Colonial Borders)

The territorial dispute between Somaliland and the neighboring Somali Federal Member State of Puntland over the eastern regions of Sool and Sanaag serves as a microcosm of the entire conflict’s core tensions. The dispute embodies the fundamental clash between the two competing principles of statehood in the region.

Somaliland’s claim is legalistic and historical, based on the inviolability of the borders inherited from the British Somaliland Protectorate. Puntland’s claim, conversely, is based on identity and kinship. It asserts authority over the regions because the dominant Dhulbahante and Warsangeli sub-clans are part of the larger Harti/Darod clan-family that forms the basis of the Puntland state. This has led to years of armed clashes, most recently the 2023 Las Anod conflict, where local Dhulbahante militias (SSC-Khatumo) rose up against Somaliland’s administration and declared their allegiance to the FGS in Mogadishu. This unresolved internal conflict highlights the fragility of Somaliland’s control over its full claimed territory and provides an entry point for Mogadishu to challenge Hargeisa’s authority.

Table 3: Positions and Interests of External Actors

| Actor | Official Position on Somaliland Recognition | Primary Strategic Interests | Key Actions/Policies |

| United States | Non-recognition (“One Somalia” policy), but under review. | Counter-terrorism (vs. Al-Shabaab); Countering China’s influence; Regional stability; Maritime security. | Maintains “One Somalia” policy but increases engagement with Hargeisa; Congressional bills support recognition; Military presence in Somalia. |

| Ethiopia | Potential recognition, conditional on sea access. | Securing sea access to reduce dependence on Djibouti; Projecting regional power; Economic growth. | Signed 2024 MoU for naval base lease in exchange for potential recognition; Maintains consulate in Hargeisa. |

| UAE | De facto recognition through investment; officially neutral. | Economic dominance (ports, logistics); Securing Red Sea trade routes; Countering Turkey/Qatar influence; Projecting military power. | Major investment in Berbera Port (DP World); Funding Berbera Corridor railway; Established naval base in Berbera. |

| Egypt | Strongly opposed; supports Somali unity. | Containing Ethiopia’s regional power (related to GERD dispute); Asserting influence in the Horn of Africa and Red Sea. | Signed defense pact with Somalia; Provides military aid to FGS; Lobbied Arab League to condemn Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU. |

| Turkey | Strongly opposed; supports Somali unity. | Expanding geopolitical influence in Africa; Economic investment; Strategic military presence; Countering UAE/Egypt influence. | Major military base in Mogadishu; Key economic and development partner for FGS; Mediating Somalia-Ethiopia tensions. |

| African Union (AU) | Strongly opposed; upholds territorial integrity of member states. | Preventing a “Pandora’s Box” of secessionist movements; Maintaining the principle of inviolable colonial borders; Regional stability. | Defers to Somali unity; Issued 2005 fact-finding report favorable to Somaliland but has not acted on it; Calls for dialogue. |

| Israel | No official position; historically recognized in 1960. | Red Sea maritime security (countering Iran/Houthis); Strategic depth; Intelligence gathering; Potential normalization partner. | Brief recognition in 1960; Informal contacts and reported intelligence operations; Somaliland has expressed openness to normalization. |

| China | Strongly opposed; supports Somali unity. | Protecting investments in Djibouti; Expanding Belt and Road Initiative; Isolating Taiwan; Gaining strategic footholds in Africa. | Veto power at UN Security Council to block recognition; Strong ties with FGS and Djibouti. |

VII. Global Interests in a Strategic Corridor

The strategic importance of the Horn of Africa, commanding the maritime chokepoint of the Bab el-Mandeb strait through which a significant portion of global trade passes, has drawn the attention of global powers. The Somaliland-Somalia dispute is no longer a localized issue but is now deeply enmeshed in the geopolitical calculations of the United States and the strategic interests of Israel. For these actors, Somaliland’s stability and location offer a unique opportunity to advance their respective agendas in a volatile but crucial region.

The United States’ Shifting Calculus: From Counter-Terrorism to Great Power Competition with China

For two decades, U.S. policy in the region was dominated by a single objective: counter-terrorism. The primary goal was to support the fragile government in Mogadishu in its fight against Al-Shabaab, viewing the FGS as the indispensable partner in this effort. This singular focus necessitated the adherence to the “One Somalia” policy, as challenging Somalia’s territorial integrity would risk alienating a key counter-terrorism ally.

However, the geopolitical landscape has shifted. The rise of great power competition with China has forced a fundamental re-evaluation of U.S. strategy. China has established its first overseas military base in Djibouti, adjacent to the U.S. base Camp Lemonnier, and has made significant economic inroads across the Horn of Africa through its Belt and Road Initiative. This has created a sense of urgency in Washington to find reliable partners to hedge against and counter Chinese influence.

In this new context, Somaliland has emerged as an increasingly attractive potential partner. Its record of stability and democratic governance stands in stark contrast to the perpetual crisis in Somalia, where billions of dollars in U.S. investment have yielded limited returns. Most significantly, Somaliland has actively courted a pro-Western alignment. In 2020, it established formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan, a move that was a direct rebuke to Beijing and a clear signal of its geopolitical orientation. This has resonated strongly with China hawks in the U.S. Congress, who now see Somaliland as a democratic, pro-Taiwan bulwark against Chinese expansionism in a vital strategic corridor. This has led to a clear divergence in U.S. policy circles: the defense and national security establishment is increasingly advocating for a pivot to Somaliland, while the diplomatic establishment remains cautious, fearing the disruption to regional norms and existing partnerships.

Israel’s Strategic Horizon: Securing the Red Sea and the Potential for Normalization

Israel’s primary interest in the Horn of Africa is the security of the Red Sea. The Bab el-Mandeb strait is a critical artery for Israeli trade with Asia, and its vulnerability has been starkly demonstrated by the recent attacks on shipping by the Iran-backed Houthi movement in Yemen. Securing this maritime flank is an existential security imperative for Israel.

Historically, Israel was one of the 35 nations that recognized the State of Somaliland during its brief independence in 1960. While no formal ties exist today, there have been periodic informal contacts, and Somaliland’s leadership has expressed openness to normalizing relations. For Israel, a partnership with Somaliland offers several strategic advantages. It could provide a location for intelligence-gathering operations to monitor Iranian and Houthi activities in the southern Red Sea, offering greater strategic depth.

A relationship with Somaliland would also align perfectly with Israel’s broader regional strategy, exemplified by the Abraham Accords. The UAE, a key Israeli partner and a signatory to the Accords, is already the dominant economic force in Berbera. An Israeli-Somaliland normalization would likely be facilitated by Abu Dhabi, creating a de facto UAE-Israel-Somaliland axis that could work to secure the Bab el-Mandeb strait and counter Iranian influence. This would provide Israel with a “southern anchor” for its regional security architecture, extending its network of partnerships into a strategically vital, non-Arab part of the wider region. While recent controversial reports suggesting Israel explored Somaliland as a potential site for resettling Gazan refugees have been denied by Hargeisa, they underscore the degree to which Somaliland now features in the strategic thinking of major regional actors.

VIII. The Domino Question: Assessing the Potential for Further Fragmentation

A central argument against the recognition of Somaliland is the fear of a “domino effect”—that its independence would inspire and legitimize other secessionist movements, leading to the violent fragmentation of Somalia and potentially other African states. However, a closer analysis of the political dynamics within Somalia’s Federal Member States (FMS) suggests this fear may be a misinterpretation. The real risk is not a series of secessions, but a “cascade of autonomy” that would render the Federal Government in Mogadishu a hollow entity. Somaliland’s case for independence is sui generis—unique in its historical and legal foundations—and therefore not easily replicable by other regions.

Analyzing Secessionist Potential in Puntland, Jubaland, and Other Federal States

Puntland: As the oldest and most established FMS, Puntland has a strong sense of regional identity and has frequently clashed with the central government over issues of autonomy, constitutional authority, and resource sharing. In March 2024, following a constitutional dispute with Mogadishu, the Puntland government announced it would no longer recognize the authority of the FGS and would “act independently” until a new federal constitution was agreed upon. However, Puntland’s political identity is fundamentally unionist. It was established in 1998 as an autonomous state

within a federal Somalia, with the goal of leading the reconstruction of a unified nation. Its foundational principle is based on the kinship of the Harti/Darod clan, and it has never harbored a cohesive independence movement akin to Somaliland’s. While some elites may advocate for secession as a pressure tactic, the mainstream political consensus remains committed to a federal Somalia in which Puntland is a powerful constituent part.

Jubaland: The political landscape of Jubaland, located in southern Somalia bordering Kenya, is even more complex. Its formation and stability have been heavily influenced by Kenyan security interests and the trans-border politics of the Ogadeen clan. Like Puntland, its leadership, under Ahmed Madobe, has had severe confrontations with the FGS, leading to a constitutional crisis in 2024 and the suspension of cooperation. These disputes, however, revolve around the control of local security forces, electoral processes, and the division of power within the federal system, not a desire for outright independence. Jubaland’s history is one of internal Somali power struggles, not a distinct colonial or national identity that could fuel a secessionist movement.

Factors Driving Autonomy vs. Full Independence

The primary political driver for other Federal Member States is a deep and abiding distrust of centralization. Having experienced the brutal dictatorship of Siad Barre and the subsequent chaos of state collapse, regional leaders are fiercely protective of their autonomy and resist any attempt by Mogadishu to consolidate power. Their struggles are for a federalism that is genuinely decentralized, giving them control over their own security and economic resources.

Unlike Somaliland, none of these other regions possess the unique combination of factors that underpin a credible case for independence: a separate colonial history, a brief period of recognized sovereignty, a legally contested act of union, and a unifying national trauma like the Isaaq genocide. Their identities are rooted in clan affiliation and their political existence was conceived

within the framework of a post-1991 federal Somalia. Therefore, their political aspirations are fundamentally different from Somaliland’s quest to restore a pre-existing statehood.

Consequences of Somaliland’s Recognition for Somali Federalism

Should Somaliland achieve international recognition, it is unlikely to trigger a wave of copycat independence declarations. Instead, it would likely accelerate the trend towards a de facto confederation in the rest of Somalia. The recognition of Somaliland would serve as definitive proof that a region can successfully defy Mogadishu, build its own institutions, and cultivate direct relationships with powerful external patrons.

Other FMS leaders, particularly in Puntland, would likely see this as a validation of their own autonomous ambitions. They would be emboldened to demand even greater powers, bypass Mogadishu in striking their own economic and security deals, and further resist federal authority. The result would be the death of the project to build a meaningful, centralized federal state. Somalia would likely evolve into a collection of semi-independent, clan-based statelets, each with its own foreign policy and external backers, with the FGS reduced to a largely symbolic entity controlling parts of the capital. This “cascade of autonomy” would formalize the political fragmentation that already exists on the ground, presenting a different, but no less profound, challenge to regional stability.

IX. Conclusion: Scenarios, Strategic Implications, and Policy Recommendations

The Somaliland-Somalia impasse has reached a critical inflection point. The long-standing, albeit fragile, status quo has been rendered untenable by the convergence of Somaliland’s unyielding quest for sovereignty and the strategic imperatives of powerful regional and global actors. The Horn of Africa is being rapidly reshaped, and the international community’s policy of passive non-recognition is no longer a viable strategy. The future trajectory of the region will likely follow one of three broad scenarios, each with profound strategic implications.

Scenario A: The Protracted Status Quo

In this scenario, no state extends formal de jure recognition to Somaliland. However, the trend of de facto engagement accelerates. The UAE continues to expand its economic and security footprint in Berbera. Ethiopia proceeds with the implementation of the MoU, developing its naval base and treating Somaliland as a sovereign partner in all but name. The United States and other Western powers increase their diplomatic and development presence in Hargeisa, citing the need to counter Chinese influence and engage with a stable regional actor. Somalia, while diplomatically protesting these moves, remains too consumed by internal conflict and reliant on foreign aid to effectively challenge this creeping normalization.

- Strategic Implications: This outcome avoids a major diplomatic rupture but institutionalizes regional instability. Somaliland remains in a state of legal limbo, unable to access international financial institutions or fully realize its economic potential. The unresolved sovereignty claim remains a persistent source of tension, susceptible to exploitation by external actors and at risk of flaring into open conflict, particularly in disputed territories like Sool and Sanaag. This scenario represents a continuation of managed instability rather than a sustainable resolution.

Scenario B: Catalytic Recognition and Regional Realignment

This scenario is triggered by a decisive move from a significant state. Ethiopia, fulfilling its side of the MoU, formally recognizes Somaliland’s independence. Alternatively, a new U.S. administration, prioritizing great power competition over traditional diplomatic norms, extends recognition. This act would break the international consensus and force other nations to take a definitive stance.

- Strategic Implications: This would precipitate an immediate and severe regional crisis. Somalia would likely sever diplomatic ties with the recognizing state(s) and could, with the backing of Egypt and Turkey, engage in military or proxy actions to assert its sovereignty. The African Union would be thrown into turmoil, its foundational principle of territorial integrity directly challenged. The Horn of Africa would become sharply polarized into two competing blocs: an Ethiopia-Somaliland-UAE axis versus a Somalia-Egypt-Turkey axis. While this would deliver Somaliland’s long-sought goal, it would come at the cost of heightened regional conflict and a new, more dangerous geopolitical fault line.

Scenario C: A Negotiated Two-State or Confederal Solution

This is the most constructive but least likely scenario in the current climate. A near-conflict event or intense, concerted diplomatic pressure from a united front of international powers (e.g., the U.S., EU, and AU) could force Somalia and Somaliland back to the negotiating table. Acknowledging the failure of past approaches, this new dialogue would be premised on finding a final status agreement that respects Somaliland’s right to self-determination while addressing Somalia’s security and identity concerns. The outcome could be a mutually agreed-upon two-state solution or a very loose confederal arrangement with two sovereign entities.

- Strategic Implications: This is the only scenario that offers a path to long-term, sustainable peace and stability. It would resolve the legal ambiguity, unlock Somaliland’s economic potential, and allow for formal cooperation on shared security threats like terrorism and piracy. However, it would require a monumental shift in Mogadishu’s political position, from asserting absolute sovereignty to accepting a negotiated partition, and would demand significant and sustained diplomatic capital from international mediators to succeed.

Policy Recommendations

- For the United States:

- Re-evaluate the “One Somalia” Policy: The policy should be critically assessed based on current U.S. strategic interests—namely countering China and ensuring maritime security—rather than on diplomatic precedent alone. The reality of Somaliland’s stability and Somalia’s enduring fragility must be central to this analysis.

- Escalate Diplomatic Engagement: The U.S. should upgrade its presence in Hargeisa from intermittent visits to a permanent liaison office. This would facilitate deeper cooperation on security and economic development without crossing the threshold of formal recognition.

- Actively Mediate and De-escalate: Washington must use its significant leverage with all parties—Ethiopia, Somalia, Egypt, and the UAE—to prevent the MoU crisis from escalating into armed conflict. The primary goal should be to forestall any unilateral actions that could trigger a regional war.

- For the African Union:

- Move Beyond the “Pandora’s Box” Doctrine: The AU must engage with the specifics of Somaliland’s case rather than relying on a blanket, 60-year-old doctrine. It should formally revisit the findings of its own 2005 fact-finding mission and acknowledge the unique legal and historical basis of Somaliland’s claim.

- Launch a Proactive Diplomatic Initiative: The AU is the body with the most legitimacy to resolve this African issue. It should appoint a high-level special envoy to mediate not just between Somalia and Somaliland, but among all the key regional stakeholders, with the explicit goal of negotiating a framework for a final status agreement.

- For the Federal Government of Somalia:

- Shift from Legalism to Pragmatism: Mogadishu’s insistence on a purely legalistic claim of sovereignty over a territory it has not controlled for over 30 years is a failing strategy. A more pragmatic approach would acknowledge the de facto reality and seek a negotiated settlement that could preserve economic and cultural ties, rather than risk losing everything in a confrontation.

- Focus on Internal State-Building: The most effective way for Somalia to make a case for unity is to become a state worth uniting with. The FGS should prioritize achieving a monopoly on violence, defeating Al-Shabaab, resolving internal federal disputes, and providing reliable services to its own citizens. A stable, prosperous, and well-governed Somalia would be a far more attractive partner for a future confederal arrangement than the current fragile state.

- SOMALILAND SOMALIA

- WARARKA

- WORLD