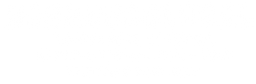

The divergent trajectories of nations in the post-colonial era present one of the most critical puzzles in international affairs. How do some countries, like Singapore, transform from impoverished, vulnerable states into global paragons of stability and prosperity, while others, like Somalia, remain mired in decades of conflict and stagnation? This report conducts an exhaustive comparative analysis of Singapore, Rwanda, and Somalia to dissect the foundational strategies that determine national success or failure. It argues that successful national transformation is not accidental but the result of a deliberate, integrated strategy founded on three core pillars: visionary and pragmatic leadership with the will to execute a long-term plan; the construction of powerful, impartial national institutions that supersede sub-national loyalties; and the forging of a unifying national identity that gives every citizen a tangible stake in the state’s survival and success.

Singapore’s journey from a precarious port city to a first-world metropolis serves as the blueprint for this model. Its success was a masterclass in holistic statecraft, where security, economic policy, and social engineering were inextricably linked and driven by a singular, unwavering vision. Rwanda, rising from the ashes of the 1994 genocide, provides a powerful corollary. Its remarkable recovery was achieved by adopting a strategy with striking parallels to the Singaporean model: strong, centralized leadership, a radical but pragmatic approach to justice and reconciliation, and a disciplined focus on rebuilding the state and its economy. Both nations demonstrate that in moments of existential crisis, a form of developmental authoritarianism, focused on delivering security and prosperity, can provide the stability necessary for transformation.

In stark contrast, Somalia represents a case of systemic and protracted failure, where these foundational principles have been consistently absent or inverted. Decades of stagnation are the product of a vicious cycle of internal fragmentation, weak and corrupt governance, extremist violence, and counter-productive foreign intervention. Somalia’s political framework, particularly the clan-based 4.5 power-sharing formula, has institutionalized the very divisions that prevent the emergence of a cohesive national government. This governance vacuum is expertly exploited by the extremist group al-Shabaab, which functions as a brutal but effective parallel state, and is further complicated by a history of foreign interventions that have often empowered spoilers and undermined organic state-building. By dissecting these contrasting cases, this report identifies the critical variables of state transformation and offers strategic pathways for navigating the complexities of modern state-building.

Part I: The Architecture of Success – The Singaporean Blueprint

The transformation of Singapore, from a resource-barren island with deep social fissures in 1965 into a global economic and financial powerhouse, stands as a seminal case study in national development. This metamorphosis was not the result of fortune or favorable geography but of a meticulously designed and ruthlessly executed integrated strategy. The Singaporean blueprint demonstrates that holistic statecraft—where security imperatives, economic planning, anti-corruption measures, and social engineering are not separate policy domains but interwoven components of a single national project—is the key to success.

Section 1.1: The Visionary State: Lee Kuan Yew and the Forging of a National Resolve

At the heart of Singapore’s success was the indispensable role of a singular, long-term vision, embodied by a leadership with the unwavering will to implement it against all odds. This vision, primarily articulated and driven by its first Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, was the prime mover of the nation’s transformation. His leadership was defined by a pragmatic, unsentimental, and farsighted perspective, encapsulated in his stark belief: “Whoever governs Singapore must have iron in them or give it up. This is not a game of cards; this is your life and mine”. This philosophy, combined with a Machiavellian conviction that it is better for a leader to be feared than loved, established the governing ethos of a disciplined, results-oriented administration that prioritized national survival above all else.

When Singapore was expelled from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, its outlook was bleak. It was a small nation with no natural resources, no domestic market, high unemployment, and festering labor unrest. In this context, Lee Kuan Yew’s vision was not based on leveraging existing assets but on a strategic wager that “superior intelligence, discipline, and ingenuity would substitute for resources”. This fundamental premise shaped every subsequent policy choice, elevating human capital, efficient governance, and unwavering stability to the status of national security imperatives. This vision was institutionalized and sustained through deliberate and careful succession planning, ensuring that the long-term strategic direction remained consistent and was not abandoned with changes in leadership—a stark contrast to states where national plans are routinely discarded by new administrations.

Lee Kuan Yew’s often “abrasive” and “blunt” communication style was not merely a personal quirk but a calculated strategic instrument. In “saying it as it is,” he stripped away the comforting illusions of political rhetoric and compelled the populace to confront the brutal reality of their circumstances. This approach served to manage public expectations and frame the national project as a desperate struggle for survival. By fostering a shared sense of crisis and national anxiety, the government was able to manufacture consent for the tough, often authoritarian, policies required for rapid industrialization and social control. Policies that might have been rejected elsewhere—such as suppressing labor unions, aggressively courting foreign capital (a move anathema to many newly independent, protectionist nations), and enforcing strict social regulations—were presented and accepted as necessary sacrifices for the collective good. The leadership’s style was therefore instrumental, not incidental, to the successful implementation of its transformative policies.

Section 1.2: The Economic Engine: From Entrepot to Global Hub

Singapore’s economic strategy was a masterclass in pragmatic statecraft, representing a deliberate and radical departure from the protectionist, import-substitution models favored by many post-colonial nations. This strategy was orchestrated by a uniquely powerful and agile state agency, the Economic Development Board (EDB), which prioritized speed, efficiency, and foreign investment to catalyze a self-sustaining ecosystem of growth.

Upon achieving independence, Singapore faced the immense challenges of mass unemployment and the sudden loss of its economic hinterland in Malaysia. In response, its leaders pivoted from a focus on the domestic market to a uniquely aggressive, export-oriented strategy centered on attracting multinational corporations (MNCs). The EDB, established in 1961 with an initial capital of $100 million, was the quasi-governmental architect of this vision. It was empowered with a direct mandate to plan and execute national economic strategies, including the development of massive industrial estates like the one in Jurong, which was built on reclaimed swampland.

The EDB’s operational doctrine was defined by extreme pragmatism and an obsession with efficiency. It went to extraordinary lengths to meet the needs of foreign companies, acting as a “one-stop shop” that could cut through bureaucratic red tape. A legendary example of this approach was the case of National Semiconductor in 1968. When the American company indicated an urgent need to begin production within two months, the EDB coordinated across all relevant government agencies and made it happen within two weeks. This feat of administrative efficiency sent a powerful signal to the global business community, attracting a wave of other major manufacturers like Texas Instruments, Hewlett-Packard, and General Electric. This pro-business environment was buttressed by a suite of supportive policies, including generous tax incentives under the 1967 Economic Expansion Incentives Act, the adoption of English as the primary language of business to facilitate global integration, and massive state investment in developing a technically skilled workforce.

A deeper analysis reveals that the EDB functioned as much more than a mere investment promotion agency; it was Singapore’s primary intelligence-gathering and strategic-planning unit for economic statecraft. Its network of international offices was not just for marketing but for actively scanning the global economic horizon to identify emerging industries and anticipate global shifts. The EDB’s history is one of constant, proactive adaptation. It initially focused on labor-intensive industries to combat unemployment. As labor costs rose, it pivoted the national strategy toward higher-value sectors like “precision engineering”. During the 1990s, it anticipated the rise of the service economy and began promoting Singapore as a hub for finance and tourism. More recently, it has astutely positioned the nation as a “test-bed” for emerging global industries, leveraging Singapore’s unique needs in areas like urban solutions and healthcare to develop exportable expertise. This pattern of exploiting crises and constantly refining its mission demonstrates a fusion of economic development with national security, where proactive economic adaptation is understood as essential for long-term survival and relevance in a competitive global landscape.

Section 1.3: The Incorruptible Pillar: Eradicating Corruption as a National Security Strategy

Singapore’s relentless and systemic war on corruption was not pursued as a matter of abstract good governance but as a foundational national security and economic survival strategy. The leadership correctly identified that in a nation with no natural resources, its only assets were its people and its reputation. Therefore, establishing unimpeachable trust, predictability, and integrity in its institutions was an absolute precondition for attracting the foreign investment essential for its economic model and for securing the legitimacy of the state in the eyes of its people.

Lee Kuan Yew framed corruption as an existential threat, stating unequivocally that Singapore could “survive only if Ministers and senior officers are incorruptible and efficient”. This was not a political slogan but a non-negotiable tenet of governance. The primary instrument for this war was the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB), an agency founded in 1952, even before independence, and later vested with immense power and operational independence to investigate any individual, regardless of their social status or political affiliation.

The CPIB’s power was anchored in robust legal frameworks, principally the Prevention of Corruption Act (PCA). The PCA was designed to be ruthlessly effective, containing several powerful legal tools that were innovative at the time. These included a presumption clause, which shifted the burden of proof by requiring a public officer accused of corruption to prove that their wealth was acquired legitimately. It also empowered courts to order convicted individuals to pay a penalty equal to the amount of the bribe they received, ensuring that crime would not pay. This zero-tolerance approach, backed by strong laws and effective enforcement, has cultivated a system where the risk of corruption across the judiciary, police, and public services is exceptionally low. This has made Singapore one of the most efficient, reliable, and attractive destinations for business in the world, directly reinforcing the economic strategy orchestrated by the EDB.

However, the anti-corruption drive also served a secondary, more political purpose: it was a formidable tool for political consolidation and control. By establishing an uncompromisingly high standard of integrity and backing it with a powerful and feared investigative body, the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) could effectively neutralize political challengers. While the judiciary is noted for its independence, analyses have observed that legal cases brought against the government or its interests “overwhelmingly result in success for the ruling party” and have, at times, led to the bankruptcy of opposition politicians. Lee Kuan Yew’s own philosophy was explicitly about maintaining control, famously stating, “If nobody is afraid of me, I’m meaningless”. The anti-corruption apparatus, while genuinely cleansing the state of graft, simultaneously functioned as a powerful deterrent against political opposition. It created a system where the rules were clear and ostensibly applied to all, but the system itself was designed and controlled by a single, dominant party. This ensured the long-term political stability that was a key selling point to risk-averse international investors.

Section 1.4: The Social Contract: Engineering Cohesion and National Identity

Recognizing that its multi-ethnic and multi-religious population was a potential source of explosive instability, Singapore’s leadership deliberately engineered a unified national identity and a unique social contract to manage these fault lines. Public housing was the primary instrument of this social engineering, used not merely to provide shelter but to give every citizen a tangible stake in the nation’s future and to enforce ethnic integration, thereby creating a shared national experience.

In the wake of the violent racial riots of the 1950s and 1960s, the government prioritized the creation of a common Singaporean identity that would transcend primordial loyalties to race, language, or religion. This ideal was enshrined in the national pledge, authored by then-Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam, which commits all citizens to be “one united people, regardless of race, language or religion”. The key institution tasked with turning this ideal into a physical reality was the Housing & Development Board (HDB). The “Home Ownership for the People Scheme,” launched in 1964, was explicitly designed to provide citizens with a tangible asset, thereby giving them a direct “stake in nation-building”. This policy has been remarkably successful, with approximately 80% of Singaporeans now living in HDB flats, the vast majority of whom are homeowners.

To prevent the formation of racial ghettoes, the government implemented the Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP), which enforces strict racial quotas in every HDB apartment block and neighborhood. This policy compels daily interaction, shared use of public spaces, and common experiences among Chinese, Malay, Indian, and other ethnic groups, breaking down barriers and fostering a common identity through proximity. This physical integration is complemented by a cultural philosophy of “integration, not assimilation,” often likened to the local dish

rojak, where distinct ingredients are mixed together to create a harmonious whole without losing their individual character. This ethos is reinforced through the school curriculum via the National Education program and through state-sponsored celebrations of the major festivals of all ethnic groups.

This strategy created a unique form of “asset-based welfare” that also functions as a powerful mechanism of social and political control. By tying the personal wealth and life savings of the vast majority of the population to state-provided housing with 99-year leases, the government forged a direct link between the financial well-being of its citizens and the stability of the state. The value of an HDB flat is inextricably linked to the country’s continued economic growth, social stability, and effective governance. Consequently, any threat to the state or its long-term plans is perceived as a direct threat to a family’s primary financial asset. This fosters a politically conservative and risk-averse citizenry, creating a powerful, self-regulating mechanism for social compliance that is far more subtle and effective than overt coercion.

Part II: The Phoenix Protocol – Rwanda’s Post-Genocide Reconstruction

The story of Rwanda’s recovery from the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi is a testament to the potential for national resurrection even from the deepest abyss of human tragedy. It is a case that offers profound lessons in state-building under the most extreme conditions. An analysis of Rwanda’s post-conflict strategy reveals a remarkable adoption of principles with striking parallels to the Singaporean blueprint: the consolidation of power under a strong, centralized leadership with a clear long-term vision; a radical and pragmatic approach to justice and social reconciliation designed to address the past without paralyzing the future; and a disciplined, state-led focus on security, institutional reform, and economic development.

Section 2.1: Leadership in the Aftermath: Paul Kagame and the Vision for a New Rwanda

In the immediate aftermath of the genocide, which claimed over a million lives and left the state utterly shattered, the leadership of Paul Kagame and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) provided the critical element of disciplined, centralized control and a clear, forward-looking vision necessary to pull the nation from complete collapse. The RPF inherited a country in ruins, facing the gargantuan tasks of establishing basic security, ending the slaughter, repatriating millions of refugees, and addressing a catastrophic humanitarian crisis.

Much like Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore, Kagame’s administration has been characterized by a strong, and often criticized as authoritarian, grip on power. This control is consistently justified by the government as essential for maintaining the stability required to prevent any relapse into ethnic violence. Crucially, this centralized authority was not an end in itself but was channeled into a comprehensive, long-term national strategy. In 2000, after extensive national consultations and seeking advice from experts from successful emerging nations, including Singapore, the government launched “Vision 2020”. This was not a vague set of aspirations but a detailed blueprint to transform Rwanda from a low-income, agriculture-based society into a middle-income, knowledge-based economy by the year 2020.

The commitment to long-term, institutionalized planning has continued. Vision 2020 has been succeeded by “Vision 2050,” an even more ambitious plan that aims to elevate Rwanda to upper-middle-income status by 2035 and high-income status by 2050. Kagame’s framing of this generational project echoes the survivalist ethos of Singapore’s early years: “Vision 2020 was about what we had to do in order to survive and regain our dignity. But Vision 2050 has to be about the future we choose, because we can, and because we deserve it”. This demonstrates a clear understanding that national recovery requires not just immediate stabilization but a compelling and sustained vision for the future.

Kagame’s leadership model suggests that in a post-catastrophe environment, the brand of “developmental authoritarianism” pioneered in Singapore can be a highly effective, if controversial, framework for recovery. The international community’s general tolerance for Kagame’s methods, despite persistent criticism of his government’s suppression of political dissent and media freedom, stems largely from his administration’s proven ability to deliver on the core tenets of this model: stability, security, significant economic growth, and low corruption. A political bargain has been struck, implicitly or explicitly, with both the Rwandan people and the international community: in exchange for limitations on political pluralism, the state guarantees peace and tangible development. While fragile, this contract has so far proven successful in steering the nation away from the abyss.

Section 2.2: Justice and Reconciliation at the Grassroots: The Gacaca Courts

Faced with an almost unimaginable judicial challenge—over 100,000 genocide suspects held in dangerously overcrowded prisons and a formal court system that had been decimated—the Rwandan government devised a radical, pragmatic, and uniquely Rwandan solution: the Gacaca court system. This initiative was not merely a legal process; it was a strategic act of state-building, indispensable for processing the trauma of the past in a way that would allow the nation to move forward.

A conventional approach to justice was simply impossible. The international community established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) to prosecute high-level planners, but it was slow and could only handle a handful of cases. The national courts were overwhelmed. In response, the government revived and heavily modified the traditional community justice system known as Gacaca (meaning “justice on the grass”), establishing over 12,000 community-based courts across the country, run by locally elected judges who often lacked formal legal training.

The goals of Gacaca were multifaceted, blending retributive and restorative justice. They aimed to establish the truth about what happened in local communities, accelerate the trial process, end the culture of impunity, and, most critically, foster reconciliation at the grassroots level. The system processed an astonishing 1.9 million cases between 2005 and 2012. It encouraged perpetrators to confess in exchange for reduced sentences and forced a direct, public confrontation between victims and perpetrators. This process, while often re-traumatizing, was intended to be cathartic, allowing victims to learn the truth about the fate of their loved ones and providing a platform for perpetrators to ask for forgiveness.

The Gacaca system was fraught with significant flaws and drew heavy criticism. Judges lacked legal expertise, fundamental fair trial rights such as the right to legal counsel were sacrificed for the sake of speed, and the process was at times manipulated to settle personal vendettas or political scores. However, viewing Gacaca solely through a legalistic lens misses its strategic purpose. It was an act of “political triage.” The Rwandan leadership recognized that pursuing perfect, individualized justice was an unattainable ideal that would lead to systemic paralysis, decades of unresolved cases, and ongoing social instability. They made a calculated decision that the risk of some miscarriages of justice was a necessary price to pay to avoid the certainty of state collapse if the overwhelming prisoner crisis was not resolved. Gacaca was therefore not primarily a legal project; it was a national security and state-building project disguised as a justice system. Its principal function was to clear the judicial backlog, enabling the state to shift its focus to the urgent tasks of reconciliation and economic development.

Section 2.3: Rebuilding the State: Forging Unity, Reforming the Economy

Rwanda’s comprehensive reconstruction strategy was built upon two pillars that mirror the Singaporean model: a radical re-engineering of national identity designed to eliminate the very source of the conflict, and a disciplined, state-led push for economic liberalization and private sector-led growth.

The post-genocide government immediately implemented a national policy of “unity and reconciliation”. This was a deliberate, top-down strategy to forge a single, unified Rwandan identity and to actively suppress the public use of ethnic labels (Hutu and Tutsi). The new constitution declared that all Rwandans share equal rights, and stringent laws were passed to criminalize “divisive genocide ideology”. The official national narrative became “We are all Rwandans,” a policy aimed at making ethnic identity politically irrelevant. This social re-engineering was supported by programs like

Ingando solidarity camps, which provided peace education to thousands of Rwandans, aiming to clarify the country’s history and promote a shared patriotism.

This profound social strategy was paired with equally aggressive economic reforms. With the support of international financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank, the government moved swiftly to liberalize the economy. It removed price controls, liberalized domestic marketing (especially in the critical coffee and tea sectors), lowered import tariffs, and established a market-determined exchange rate. These measures were designed to create a business-friendly environment conducive to private sector development and to attract the foreign aid and investment needed for reconstruction.

The results of this dual strategy were dramatic. Between 1995 and 2008, Rwanda’s annual GDP growth averaged over 8 percent. By 1998, GDP had already recovered to its pre-genocide level. Poverty rates fell significantly, from 78 percent after 1994 to 38 percent by 2017, and key social indicators such as child mortality rates and primary school enrollment saw drastic improvements.

The contrast between Rwanda’s approach to identity and that of Somalia is stark and revealing. Where Somalia’s political solution, the 4.5 formula, institutionalized sub-national clan identity as the fundamental basis of politics, Rwanda sought to eradicate politicized ethnic identity from the public sphere. This demonstrates a core principle of successful post-conflict state-building: the political organizing principle of the state must be the unified nation, not its constituent identity groups. The Rwandan leadership identified politicized ethnicity as the root cause of the genocide and made the logical, albeit radical, decision to remove it as a political variable. Somalia, by contrast, chose a path of least resistance that legitimized and entrenched the very source of its divisions. This fundamental strategic divergence is perhaps the single most important factor explaining their vastly different outcomes.

Part III: The Anatomy of Protracted Crisis – Deconstructing Somalia’s Stagnation

For more than three decades, Somalia has been the archetype of a failed state, trapped in a seemingly unbreakable cycle of violence, famine, and political fragmentation. This protracted crisis is not the result of a single cause but of a complex web of interlocking factors that mutually reinforce one another. A deep analysis reveals a vicious cycle where deep-seated internal fragmentation, epitomized by clan politics, fosters weak and predatory governance. This governance vacuum, in turn, creates the ideal conditions for the rise of violent extremist groups like al-Shabaab, which then perpetuate the conflict. This entire catastrophic system is further destabilized by a long history of counter-productive foreign interventions that have often exacerbated the very problems they sought to solve.

Section 3.1: The Fractured State: The Legacy of Collapse and Clan Politics

The collapse of the Somali state in 1991 was not a singular event but the violent culmination of historical grievances that were exacerbated, not resolved, by the post-colonial state. The roots of this collapse can be traced to the arbitrary colonial partition of Somali-inhabited territories, the imposition of a centralized state model that was alien to the region’s decentralized pastoral traditions, and the brutally repressive and clan-favoring dictatorship of Siad Barre, which systematically dismantled traditional institutions and politicized clan identity for its own survival.

In the power vacuum that followed Barre’s ouster, clan identity, which had always been a central feature of Somali culture, re-emerged as the primary, and often only, unit for political mobilization, social loyalty, and physical security. The traditional

dia-paying group—a kinship-based collective security arrangement—became the most effective form of social contract in a stateless society. In an attempt to manage the ensuing civil war, the international community and Somali elites devised the “4.5 power-sharing formula.” This political framework was intended as a pragmatic tool to distribute parliamentary seats and government positions among Somalia’s four major clan families (the “4”) and a coalition of smaller minority clans (the “0.5”).

While this formula has been instrumental in mediating elite-level conflicts and allowing for the formation of successive transitional governments, it has simultaneously institutionalized the very divisions that prevent the emergence of a cohesive and functional national state. The 4.5 system is widely criticized for reinforcing clan identity as the sole legitimate basis for political participation, thereby hindering the development of a meritocratic civil service, causing chronic political stagnation, and systematically marginalizing smaller clans and women. It has created a political culture where national interest is perpetually subordinated to clan interest.

This reveals a fundamental failure of political imagination and will. The 4.5 formula is a conflict management system, not a state-building project. By locking in clan identity as the organizing principle of the state, it prevents the emergence of a broader national consciousness or the formation of political parties based on ideology, policy platforms, or economic interests. A politician’s power and legitimacy derive entirely from their clan affiliation, not from a national constituency. Their primary accountability is therefore to their clan, not to the nation. This structure makes national-level projects—such as building a truly national army, implementing a unified economic plan, or fighting corruption—nearly impossible, as every initiative is viewed through the zero-sum lens of which clan stands to benefit most. The system is designed for stasis, successfully preventing a full-scale return to the all-out war of the early 1990s but also preventing any meaningful progress forward, thus creating the decades-long stagnation that defines Somalia’s modern history.

Section 3.2: The Internal Spoilers: Governance Deficits and Violent Extremism

The weak, clan-based federal government, hamstrung by its own internal divisions and pervasive corruption, is incapable of providing the most basic functions of a state, such as security and public services. This has created a profound governance vacuum across large swathes of the country, a vacuum that the extremist group Harakat Shabaab al-Mujahidin (al-Shabaab) has expertly and brutally exploited, establishing itself as a formidable parallel state.

The authority of the central government in Mogadishu is largely nominal, with its effective control limited to the capital and a few other urban centers. The state-building process is perpetually crippled by intractable power struggles between the federal government and the federal member states, which often operate as semi-autonomous fiefdoms. This political paralysis is compounded by systemic corruption; Somalia consistently ranks at or near the bottom of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, a reality that has destroyed public faith in state institutions.

Al-Shabaab, an al-Qaeda affiliate, has become deeply entrenched by capitalizing on these governance failures. It is not merely a clan-based insurgent group but a sophisticated organization that provides its own form of governance. In the territories it controls or influences, it collects taxes, adjudicates disputes through its own courts, and enforces a harsh but predictable form of order. The group’s resilience stems from its political adroitness at exploiting clan rivalries, offering support and a sense of justice to marginalized clans that feel excluded by the official 4.5 system.

This makes al-Shabaab more than just a terrorist group; it is a political-economic enterprise that has a vested interest in the continued weakness of the central state. It has successfully monetized state failure. Its taxation system is reportedly more efficient and predictable in the areas it controls than the government’s, generating an estimated $100 million in annual revenue. This creates a perverse incentive structure where, for many ordinary Somalis and businesses, paying taxes to al-Shabaab may be a rational economic decision if it guarantees security and contract enforcement—services the official government cannot reliably provide. This means al-Shabaab’s power is not just military; it is administrative and economic. Defeating the group requires not just a military campaign but the construction of a state that can effectively

out-govern it—a task for which the current Somali political structure is fundamentally ill-equipped.

Section 3.3: The External Quagmire: A History of Counter-Productive Intervention

Decades of foreign intervention in Somalia have consistently failed to bring stability and have often exacerbated the country’s internal conflicts, empowered spoilers, and undermined organic, locally-driven state-building efforts. From Cold War patronage politics to post-9/11 counter-terrorism operations and the proxy rivalries of regional powers, external involvement has become a central and destructive feature of the Somali political landscape.

This long and troubled history includes the initial colonial partitions and the Cold War period, during which both the United States and the Soviet Union supported the Siad Barre dictatorship at different times, contributing to the militarization of the state. The most emblematic failure was the US-led UN intervention from 1992 to 1995 (UNOSOM I & II). What began as a humanitarian mission to alleviate famine quickly morphed into an ambitious “nation-building” and peace-enforcement operation. The mission failed to grasp the complexities of local clan dynamics, inadvertently empowered the very warlords it sought to sideline, and ended in a humiliating withdrawal following the “Black Hawk Down” incident in October 1993.

There appears to be an “eerie correlation” between intensified international intervention in Somalia and the deterioration of conditions on the ground. Interventions have often been externally driven, poorly designed, and implemented without securing genuine local consent or understanding. Regional powers, particularly Ethiopia and Kenya, have repeatedly intervened militarily, often with the backing of Western nations. While ostensibly aimed at combating al-Shabaab, these interventions are also driven by their own national security interests and historical rivalries, and are viewed with deep suspicion by many Somalis. This has fueled a nationalist backlash that al-Shabaab skillfully exploits. More recently, Somalia has become an arena for the geopolitical rivalries of Gulf states (such as the UAE and Qatar) and other powers like Turkey, Iran, and Russia, with different external actors backing competing political factions or federal states, further fragmenting the country and undermining the authority of the central government.

Somalia suffers from a pathology of international intervention. External actors consistently misdiagnose the core problem. They perceive Somalia as a technical problem—a ‘failed state’ that needs a ‘fix’ like an election, a new constitution, or a trained army—and they attempt to impose this fix from the top down. However, the fundamental issue is the absence of a legitimate and inclusive political settlement among Somalis. By backing specific factions, providing aid that fuels corruption, and prioritizing their own narrow security interests (primarily counter-terrorism), external actors continuously disrupt the difficult, messy, and essential internal process of negotiation and consensus-building. This is the only viable path to a stable state. In effect, the international community has spent decades treating the symptoms of the crisis (famine, piracy, terrorism) while its interventions have inadvertently perpetuated the underlying disease: a fractured and unresolved political compact.

Part IV: A Comparative Synthesis – Critical Variables of State Transformation

The starkly different outcomes in Singapore, Rwanda, and Somalia are not accidents of history, geography, or culture. They are the direct results of deliberate strategic choices made by their leaders and political elites at critical junctures. A comparative synthesis of these cases reveals a set of decisive variables that distinguish state transformation from state stagnation. These variables fall into three main categories: the quality of leadership and vision, the approach to institution-building versus identity politics, and the understanding of the security-development nexus.

Section 4.1: Leadership and Vision: The Decisive Factor

The single most critical variable is the presence of a visionary, pragmatic, and determined leadership. In Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew provided a clear, long-term, nation-first vision focused on survival and excellence. His leadership was characterized by an “iron” will to see this vision through, making difficult and unpopular decisions for the sake of long-term national gain. Similarly, in Rwanda, Paul Kagame’s leadership provided a disciplined, post-genocide resolve, channeling the nation’s trauma into a forward-looking vision of unity and transformation, as articulated in Vision 2020 and Vision 2050. Both leaders prioritized building durable institutions that would outlast them. In sharp contrast, Somalia has been plagued by fragmented, competitive elites and warlords whose vision is typically limited to short-term, clan-centric power acquisition. Their political energy is consumed by bargaining for control over the spoils of a failing state, rather than uniting to build a functional one for the future.

Section 4.2: Institutions vs. Identity: Building the State vs. Managing the Clan

The second fundamental divergence lies in the primary political organizing principle. Singapore and Rwanda both prioritized the construction of strong, impartial national institutions designed to transcend sub-national identities. Singapore pursued a policy of state-led multicultural nationalism, where ethnic identities are managed and integrated to serve the overarching goal of national cohesion. Rwanda took an even more radical approach, enforcing a de-ethnicized national unity under the banner “We are all Rwandans,” actively suppressing ethnic identification in the political sphere to prevent a recurrence of conflict.

Somalia chose the opposite path. Its political framework, the 4.5 formula, institutionalizes and politicizes sub-national clan identity, making it the very foundation of the state. The state, therefore, does not stand above the clans but serves as an arena for their competition. This makes the creation of a unified national identity or a truly national set of institutions impossible, as loyalty remains primarily with the clan, not the state.

Section 4.3: The Security-Development Nexus

Finally, the cases demonstrate a clear sequence for successful transformation. In both Singapore and Rwanda, establishing a state monopoly on violence, ensuring the rule of law, and eradicating corruption were understood as non-negotiable preconditions for sustainable economic development. Singapore’s zero-tolerance policy on corruption was explicitly linked to its economic survival strategy. Rwanda’s post-genocide government prioritized security, justice (via Gacaca), and institutional reform before it could credibly embark on its ambitious development plans. In Somalia, this sequence is reversed. The persistent lack of a foundational security architecture—marked by the presence of clan militias and the powerful insurgency of al-Shabaab—and the absence of the rule of law render any national development strategy moot. The economy remains fragmented, aid-dependent, and dominated by illicit activities and parallel taxation by spoilers, trapping the country in a state of arrested development.

Part V: Conclusion and Strategic Pathways

Section 5.1: Synthesis of Findings

This comparative analysis of Singapore, Rwanda, and Somalia yields a clear and powerful conclusion: successful national transformation is not predetermined by geography, culture, or natural resource endowments. It is, fundamentally, a product of strategic choice. The vast chasm between Singapore’s prosperity, Rwanda’s recovery, and Somalia’s protracted crisis can be explained by the presence or absence of a critical triumvirate of strategic pillars:

- Visionary, Pragmatic Leadership: The capacity of a nation’s leadership to define, articulate, and ruthlessly enforce a long-term national project that transcends short-term political calculations and sectarian interests is the primary determinant of its trajectory. Lee Kuan Yew and Paul Kagame, for all their differences, both provided this decisive, unifying force. Somalia’s tragedy is, in large part, a tragedy of leadership, marked by its chronic absence.

- An Institution-First Approach: The most successful states are built on the foundation of strong, impartial national institutions that command the primary loyalty of citizens. Singapore and Rwanda both understood that the state must stand above sub-national identities. They built powerful security, judicial, and economic institutions that served the entire nation. Somalia’s political framework does the opposite, making the state subservient to clan identity, thereby rendering the construction of effective national institutions impossible.

- A Unifying National Narrative and Social Contract: A nation must be more than a geographical entity; it must be an idea that its people are willing to invest in. Singapore engineered a social contract based on home ownership and shared prosperity. Rwanda is attempting to forge a new, unified identity from the ashes of genocide. Both gave their citizens a tangible stake in the nation’s success. Somalia lacks a compelling national narrative beyond the zero-sum competition of clan, leaving its people with little reason to invest their trust or hope in a failing central state.

Ultimately, the lesson is that state-building is an act of deliberate creation. Singapore and Rwanda, facing existential threats, chose to build. Somalia, caught in a cycle of internal division and external interference, has been unable to make that foundational choice.

Section 5.2: Strategic Pathways for Fragile States

The insights derived from this analysis offer several high-level, actionable recommendations for policymakers and international actors engaged in fragile states like Somalia.

- Prioritize a Political Settlement over Technical Fixes: The international community must fundamentally shift its approach. Instead of prioritizing technical solutions like holding another election based on a flawed formula or delivering aid through corrupt channels, the primary focus must be on facilitating an inclusive, Somali-led process to forge a new political settlement. This process must aim to move beyond the 4.5 formula and establish a new basis for the state that is seen as legitimate by a broad cross-section of Somali society.

- Insulate Development from Spoilers: To break the cycle of aid fueling corruption and conflict, future development assistance must be redesigned to be “spoiler-proof.” This could involve shifting focus from large-scale support to the central government towards hyper-local, community-driven projects that bypass predatory central structures. Empowering local communities to manage resources and see tangible benefits can build state legitimacy from the bottom up and create resilience against spoilers like al-Shabaab.

- Sequence Reforms: Security and Justice First: The Singaporean and Rwandan models demonstrate that a baseline of security and a predictable system for dispute resolution are non-negotiable preconditions for all other forms of development. International efforts should be sequenced accordingly. The absolute priority must be to support the creation of a legitimate, unified national security force and a trusted, accessible justice system. Without this foundation, investments in economic development or social programs will fail to take root.

- Contain Negative External Influence: The international community, particularly the UN Security Council and major regional bodies, must undertake a concerted diplomatic effort to create a “cordon sanitaire” around Somalia. This means establishing a unified international stance that actively penalizes regional and international powers that treat Somalia as a chessboard for their proxy conflicts by backing rival factions. Ending the destructive cycle of foreign interference is essential to give Somalis the political space they need to negotiate their own future.